Egypt

Area C. The area immediately to the east of the Small Palace built from limestone blocks had been barely examined by the Pendlebury expedition. Last year, a new set of basins was found to the north of one that had been found before. The next strip of ground to the north has now revealed a further set. As this work has proceeded, the top of the wide area of mud brickwork that has the appearance of a wall around the northern gypsum concrete platform has been cleaned and planned. This extends into:

Area C. The area immediately to the east of the Small Palace built from limestone blocks had been barely examined by the Pendlebury expedition. Last year, a new set of basins was found to the north of one that had been found before. The next strip of ground to the north has now revealed a further set. As this work has proceeded, the top of the wide area of mud brickwork that has the appearance of a wall around the northern gypsum concrete platform has been cleaned and planned. This extends into:

We have had signs before that the rubble that separates the two main temple phases includes broken stonework, some of fine quality, from the earlier temple. Where we have encountered it, however, it represents a relatively small component of the rubble although sometimes found in dense pockets. Some of the damage to stonework, as in the case of the statue, could have been accidental, brought about as large pieces of stone were taken down. But other pieces look like the result of deliberate breakage into relatively small pieces.

We have had signs before that the rubble that separates the two main temple phases includes broken stonework, some of fine quality, from the earlier temple. Where we have encountered it, however, it represents a relatively small component of the rubble although sometimes found in dense pockets. Some of the damage to stonework, as in the case of the statue, could have been accidental, brought about as large pieces of stone were taken down. But other pieces look like the result of deliberate breakage into relatively small pieces.

This implies that the reconstructions of the second temple that show the field of mud-brick offering-tables on one or both sides are wrong. The tables belong instead to an earlier temple layout. They had been buried and must have been invisible by the time that the second temple was built. It was into this flat terrace that the gypsum-lined circular basins were made.

This implies that the reconstructions of the second temple that show the field of mud-brick offering-tables on one or both sides are wrong. The tables belong instead to an earlier temple layout. They had been buried and must have been invisible by the time that the second temple was built. It was into this flat terrace that the gypsum-lined circular basins were made.

As the results of our own re-investigation of the Great Aten Temple accumulate, it is possible to see the signs of two somewhat different dynamics emerging. There is the one that we expect: the drive to create a single temple along classic lines, monumental in scale and symmetrical about an approximate east-west axis. It gave rise, in some of the rock tombs, to pictures that show a completed Aten temple, with a functioning cult. It saw a major rebuild that included the colonnade of colossal sandstone columns in front of the stone façade of the renewed temple. The huge foundation platforms of gypsum concrete have no parallel at the Small Aten Temple and this could be a sign of concern raised by structural weakness at the earlier colonnade, perhaps even its collapse. In order to rebuild the colonnade on its new site, probably further to the west than its predecessor, a huge box was created by building a mud-brick surrounding wall, about 3 m thick, with an equally broad access ramp at the north-west corner. The box itself could have been filled with sand. Once the colonnade was completed, the wall and ramp were taken down, the bricks perhaps supplying a good part of the fill that created the new, raised ground level, the sand (that was mixed with broken pieces of stonework) perhaps used for the fill of the stone offering-table courts to the east.

As the results of our own re-investigation of the Great Aten Temple accumulate, it is possible to see the signs of two somewhat different dynamics emerging. There is the one that we expect: the drive to create a single temple along classic lines, monumental in scale and symmetrical about an approximate east-west axis. It gave rise, in some of the rock tombs, to pictures that show a completed Aten temple, with a functioning cult. It saw a major rebuild that included the colonnade of colossal sandstone columns in front of the stone façade of the renewed temple. The huge foundation platforms of gypsum concrete have no parallel at the Small Aten Temple and this could be a sign of concern raised by structural weakness at the earlier colonnade, perhaps even its collapse. In order to rebuild the colonnade on its new site, probably further to the west than its predecessor, a huge box was created by building a mud-brick surrounding wall, about 3 m thick, with an equally broad access ramp at the north-west corner. The box itself could have been filled with sand. Once the colonnade was completed, the wall and ramp were taken down, the bricks perhaps supplying a good part of the fill that created the new, raised ground level, the sand (that was mixed with broken pieces of stonework) perhaps used for the fill of the stone offering-table courts to the east.

Then there are the offering-tables that were built on the lower mud floor. The finding of mud-brick offering-tables on the north does not quite confirm that they formed a mirror-image set to those on the south. On the limited evidence so far available, they were smaller, they lay closer to the outline of the later temple and, although there is still much ground to be tested, it looks as if the twin lines of thick gypsum bases for stone offering-tables built on the lower mud floor to the south were not duplicated on the north. If the two fields of offering-tables, on the north and on the south, were not identical, how can we be sure that they were built and used at the same time? Should we start to think that the outside spaces had a history of use of their own, with their own rules for spatial arrangement, separate from the history of the formal stone buildings? One visitor placed a child’s burial in a shallow grave under the floor beside the southern ones.

Then there are the offering-tables that were built on the lower mud floor. The finding of mud-brick offering-tables on the north does not quite confirm that they formed a mirror-image set to those on the south. On the limited evidence so far available, they were smaller, they lay closer to the outline of the later temple and, although there is still much ground to be tested, it looks as if the twin lines of thick gypsum bases for stone offering-tables built on the lower mud floor to the south were not duplicated on the north. If the two fields of offering-tables, on the north and on the south, were not identical, how can we be sure that they were built and used at the same time? Should we start to think that the outside spaces had a history of use of their own, with their own rules for spatial arrangement, separate from the history of the formal stone buildings? One visitor placed a child’s burial in a shallow grave under the floor beside the southern ones.

Several members of the expedition have come to work within the expedition house. Andy Boyce completed nearly a month of drawing finds both from the South Tombs Cemetery and from the temple. Alexandra Winkels, on a research visit, was able to set up a portable laboratory in the house that allowed her to pursue her scientific studies of ancient plasters, especially those that go under the heading ‘gypsum’. Marsha Hill and Kristin Thompson have continued their studies on the statues and other hard stone pieces of sculpture that we have stored in the site magazine. Geologist Jim Harrell has made a return visit to investigate sources of gypsum and indurated limestone. Jackie Williamson has been able to visit and discuss her work at Kom el-Nana as a result of involvement with a new film being made on the subject of Queen Nefertiti.

Several members of the expedition have come to work within the expedition house. Andy Boyce completed nearly a month of drawing finds both from the South Tombs Cemetery and from the temple. Alexandra Winkels, on a research visit, was able to set up a portable laboratory in the house that allowed her to pursue her scientific studies of ancient plasters, especially those that go under the heading ‘gypsum’. Marsha Hill and Kristin Thompson have continued their studies on the statues and other hard stone pieces of sculpture that we have stored in the site magazine. Geologist Jim Harrell has made a return visit to investigate sources of gypsum and indurated limestone. Jackie Williamson has been able to visit and discuss her work at Kom el-Nana as a result of involvement with a new film being made on the subject of Queen Nefertiti.

- Work At Amarna In March 2013

With thanks to Barry Kemp and Anna Stevens for the latest Amarna update. Apologies that the images at then end are not in the right order but you will find that the figure numbers correspond to the captions. The first part of the 2013 season ended...

- Amarna 2013 Begins

2013 STARTUP It has proved possible to resume fieldwork at Amarna. Barry Kemp and a small team traveled to the expedition house on Wednesday, January 30th and began work on site on Saturday, February 2nd, with 20 local workmen, mostly from El-Till and...

- Autumn Field School At Amarna

The latest news update from Professor Barry Kemp, from the Amarna Project. On October 14th the current Amarna field school began to assemble, five overseas students and seven SCA inspectors (drawn mostly from the Middle Egypt region) converging on the...

- A Report On Work Recently Completed At Amarna, Spring 2012

By Barry Kemp A REPORT ON WORK RECENTLY COMPLETED AT AMARNA, SPRING 2012 Figure 1 (see captions at end of article)On the last day of March we resumed our fieldwork. The chosen place was the site of the Great Aten Temple, that lies immediately beside...

- Amarna Field School And News

www.amarnatrust.com and www.amarnaproject.com Update by Barry Kemp, 4 March 2012: FIELD SCHOOL As a follow-on from last year's Amarna field school, we are holding another this year, between October 14th and November 22nd (five weeks). Again it will...

Egypt

Amarna, Spring Season 2014, second report from Barry Kemp

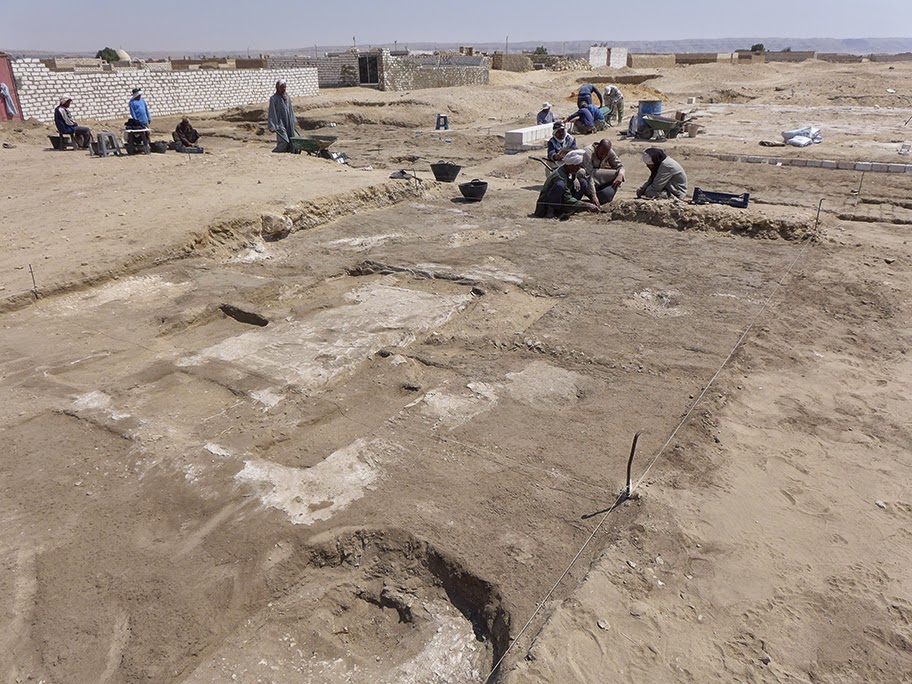

We are now nearing the end of the 2014 spring season. The fieldwork has been concentrated at the Great Aten Temple. Several excavating teams, under the supervision of Miriam Bertram, Delphine Driaux, Anna Hodgkinson and Sue Kelly, assisted by Juan Friedrich and Julia Vilaró, have been deployed across the front area. Three Ministry of Antiquities inspectors (Joseph Elya Mikhail, Randa Mohammed Abd el-Rahim and Abdullah Ali Abd el-Rahman Maaruf) have joined us for training. Inspector Ahmed Mustafa Abd el-Aziz is responsible for the fieldwork, and Hammada Abd el-Azim Abd el-Hafiz for the magazines.

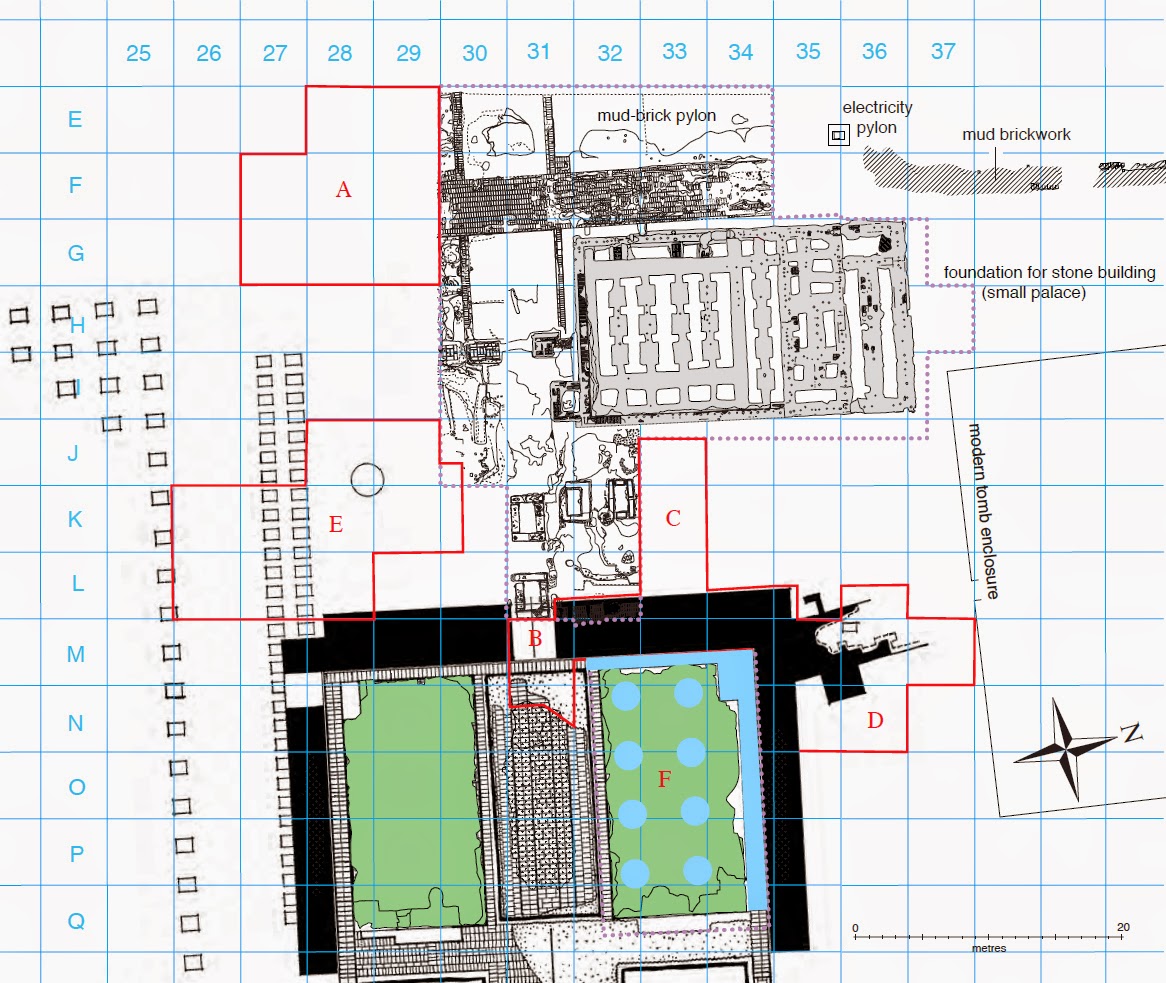

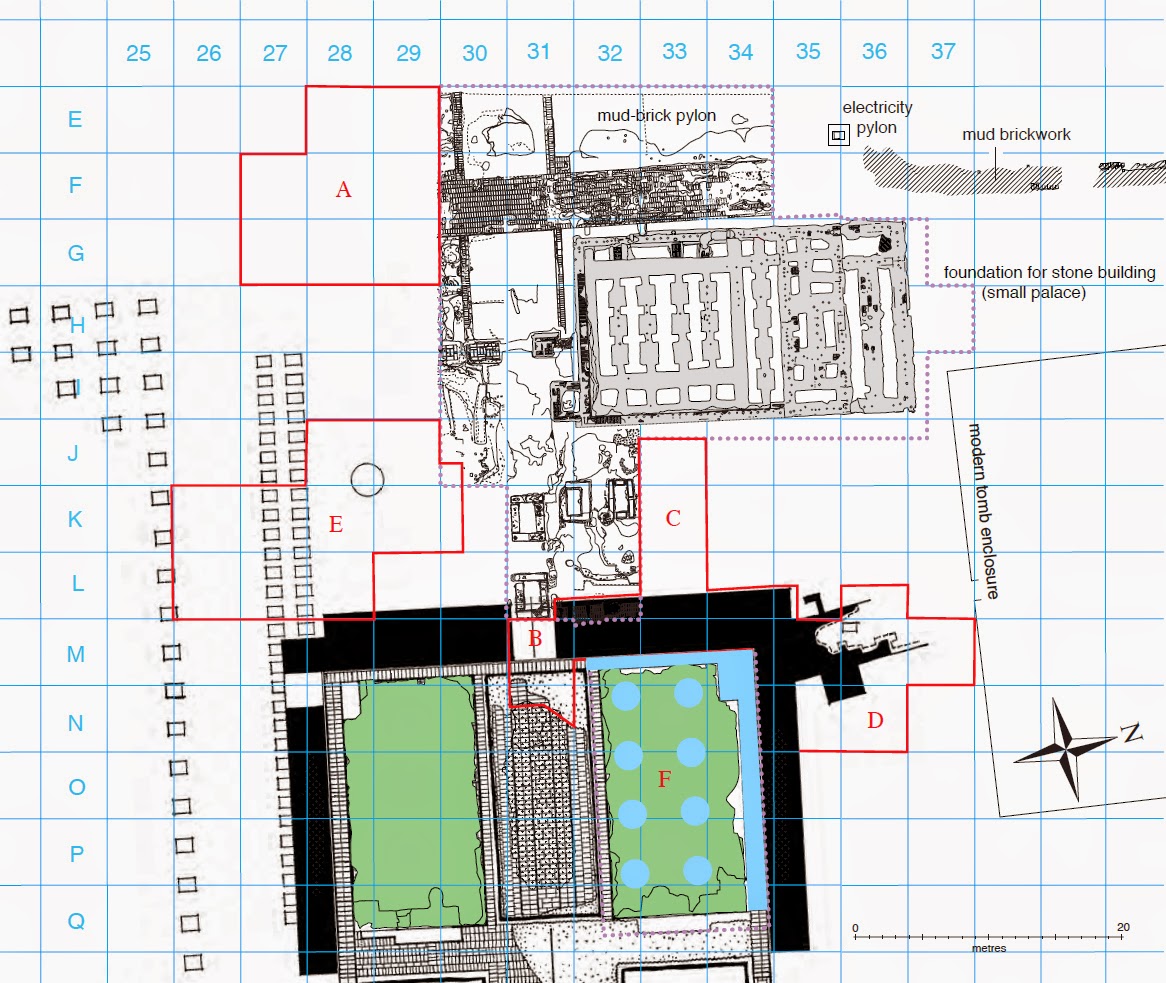

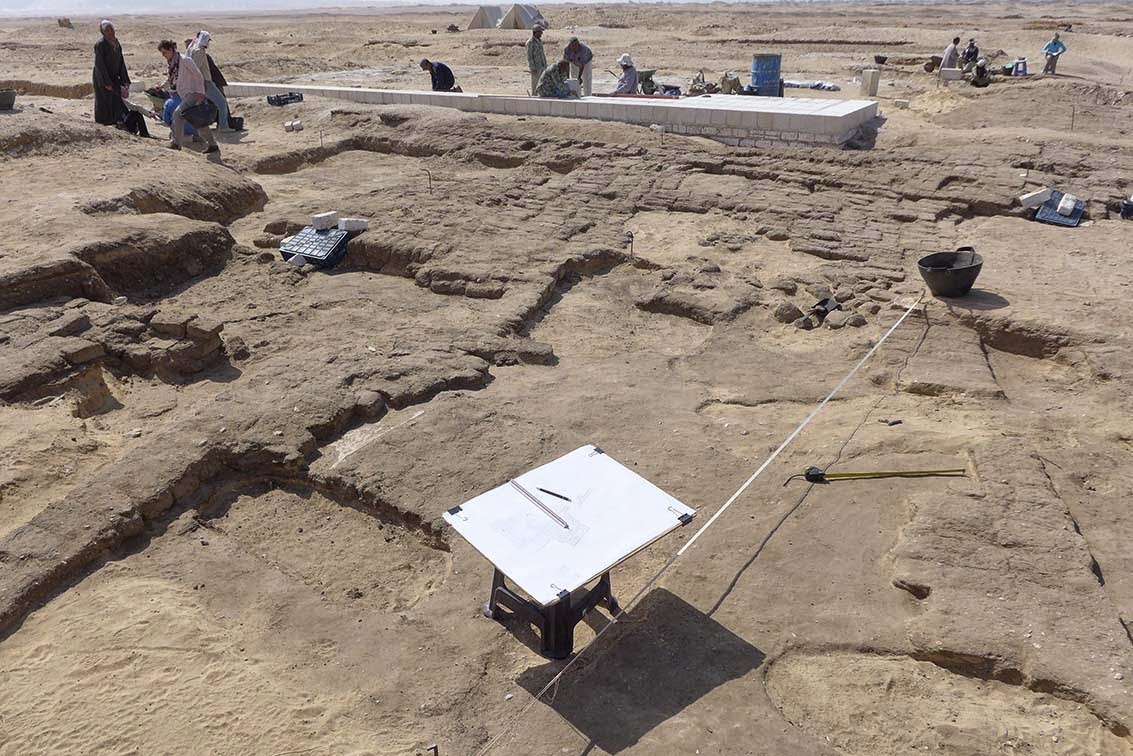

The re-examination of the temple, that includes the removal of Pendlebury spoil heaps, is spread across several areas, the pattern of work to some extent dictated by the trenches and spoil heaps of the 1932 excavation. The attached map indicates the location of each area compared to the plan of the 1932 excavation.

Area A. A large spoil heap that had buried the southerly of the two mud-brick outer pylons has now been removed, exposing the remains of the pylon. At some time in the past, what looks like a long puddling pit has been made in the middle, in which bricks have been turned into a mud mix, perhaps for the making of newer bricks at a more convenient size. A good stratigraphic section has come to light that adds to the understanding of the history of building.

Area B. Last year and the year before most of Pendlebury’s trench along the axis of the temple was re-excavated. Amongst the features exposed and recorded were two sets of gypsum-lined basins, each set arranged around a central rectangular island. The final part of this axial trench has now been cleaned, revealing a third set of basins that had been filled in during the Amarna Period, had been cut by a later foundation trench and were only partially seen in 1932. The excavation here has also been extended a short way to the east, into the sand fill beneath a gypsum concrete layer that formed the basis for a stone ‘causeway’ that ran between two sets of huge columns on sturdy concrete foundations (Area F). The sand fill, in turn, buried more of the mud floor of the first temple.

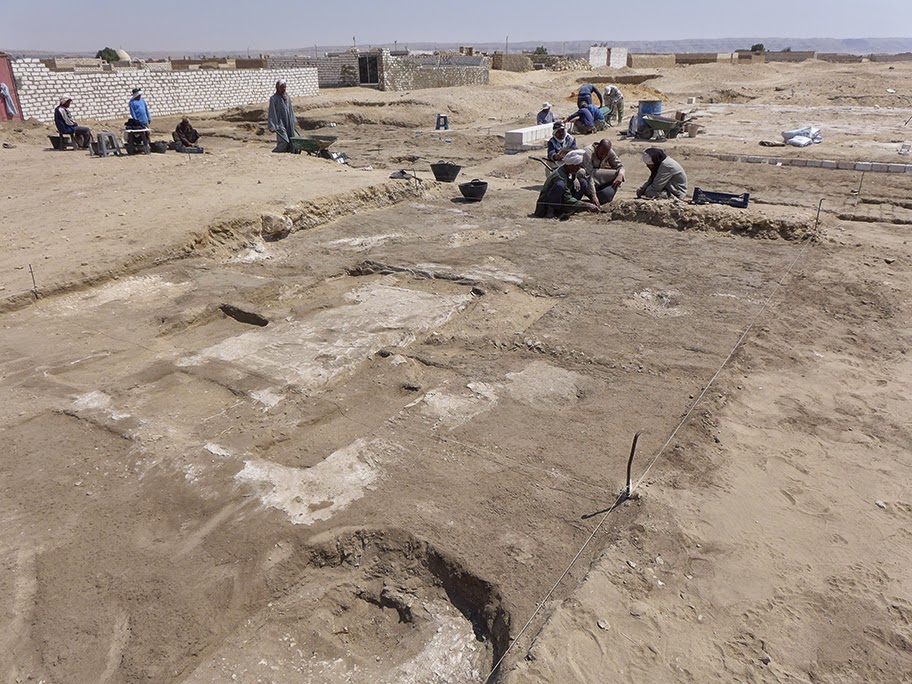

Area C. The area immediately to the east of the Small Palace built from limestone blocks had been barely examined by the Pendlebury expedition. Last year, a new set of basins was found to the north of one that had been found before. The next strip of ground to the north has now revealed a further set. As this work has proceeded, the top of the wide area of mud brickwork that has the appearance of a wall around the northern gypsum concrete platform has been cleaned and planned. This extends into:

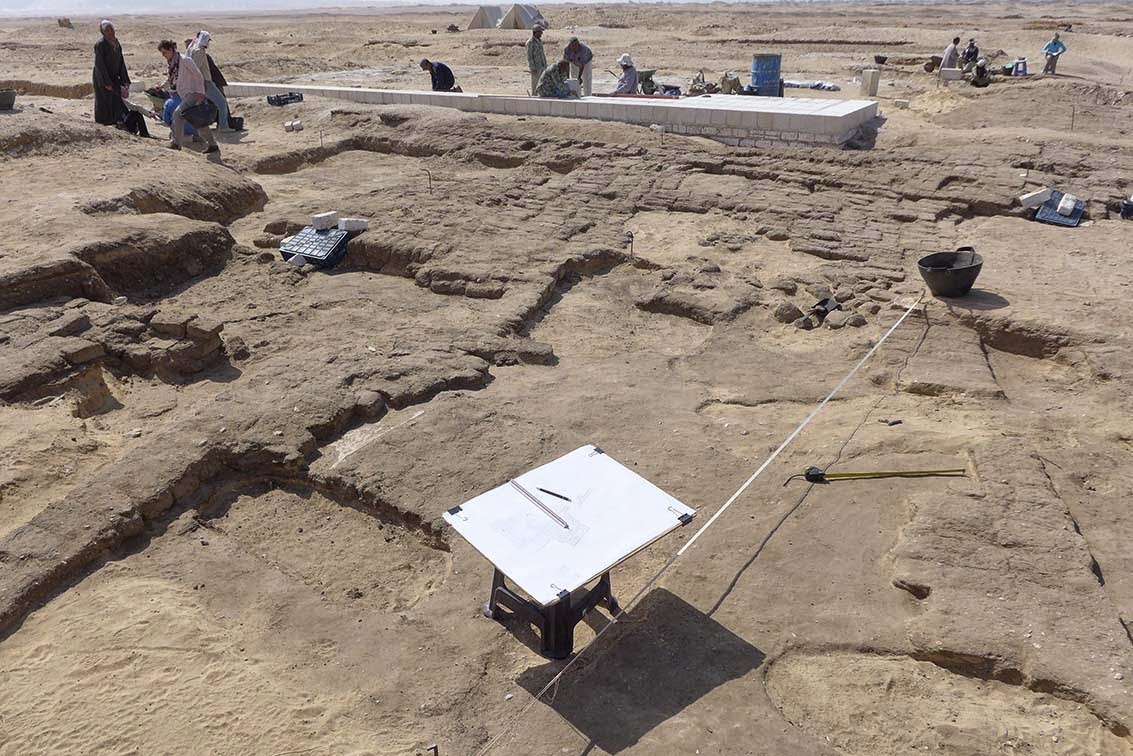

Area C. The area immediately to the east of the Small Palace built from limestone blocks had been barely examined by the Pendlebury expedition. Last year, a new set of basins was found to the north of one that had been found before. The next strip of ground to the north has now revealed a further set. As this work has proceeded, the top of the wide area of mud brickwork that has the appearance of a wall around the northern gypsum concrete platform has been cleaned and planned. This extends into:Area D. A spread of brickwork runs further to the north, at an angle to the temple axis. It was exposed and planned by the Pendlebury expedition, who were uncertain as to what purpose it served or even it if were contemporary with the temple. The northern part of this area contains many graves, small enough to be of children, cut into the brickwork and ancient floors. They belong probably to an extension to the village cemetery of recent centuries that lies close by. Fortunately, they descend below the archaeological layers so that it is possible to study the latter without disturbing them. One explanation for this brickwork is that it is the remains of temporary walls, served by a ramp, that helped the builders erect the large columns in front of the stone pylon.

The Great Aten Temple is famous for the large number of its offering-tables. In addition to those made of limestone blocks that were situated close to the temple axis, a field of 920 made from mud bricks spread across the open ground to the south. Pendlebury thought that a similar field had lain on the north side and claimed to have found ‘enough… to show that the same system obtained’, but provided no details. An aerial photograph of the temple taken not long afterwards shows no sign of them, in contrast to the many signs of the offering-tables to the south. In the absence of definite evidence it has seemed prudent to doubt the existence of the northern field. We now have the definite evidence for their existence on this side. The mud-brick ‘ramp’ had been built over the top of at least three of them. In the case of one of them, a well preserved stretch of white plastered surface is adjacent to it. The fact that traces of this group survive beneath the mud-brick ramp that belongs to the second temple tells us an important fact about them. They belong to the first temple and not to the second. In being on the north side, they were built on slightly higher ground and have therefore suffered from erosion as well as destruction from the modern cemetery. This is why no traces show up on old aerial photographs.

Area E. This part takes in both a low-lying area left by another wide Pendlebury trench and the slopes of another dump lying to the north. The dump had covered two more sets of gypsum-lined basins belonging to the later temple, as well as a deep circular one that appears in the Pendlebury narrative. A second circular basin, seen and photographed by Pendlebury but not reported, lies towards the southern margin of this excavation area. Between them the original desert floor had been covered with a mud surface and also with rectangular patches of gypsum concrete that were the foundations for two parallel lines of offering-tables built from limestone blocks and a conspicuous element of the earlier temple. We have exposed all or a part of seven of them in each row.

Further to the south, our excavation moved beyond the southern limit of Pendlebury’s wide trench. The material to be removed, that covers the early mud floor, is more of the layer of sand and rubble that was used to build up the ground for the later temple. Here it seems to be largely undisturbed. Within the rubble, in addition to mud bricks, lay pieces from sandstone columns of large diameter, part of a limestone cornice or architrave bearing the cartouches of the Aten (probably the later version), a piece of balustrade carved in indurated limestone and the mid-part of a limestone statue, roughly two-thirds life size, of a royal woman clad in an elaborately pleated garment.

We have had signs before that the rubble that separates the two main temple phases includes broken stonework, some of fine quality, from the earlier temple. Where we have encountered it, however, it represents a relatively small component of the rubble although sometimes found in dense pockets. Some of the damage to stonework, as in the case of the statue, could have been accidental, brought about as large pieces of stone were taken down. But other pieces look like the result of deliberate breakage into relatively small pieces.

We have had signs before that the rubble that separates the two main temple phases includes broken stonework, some of fine quality, from the earlier temple. Where we have encountered it, however, it represents a relatively small component of the rubble although sometimes found in dense pockets. Some of the damage to stonework, as in the case of the statue, could have been accidental, brought about as large pieces of stone were taken down. But other pieces look like the result of deliberate breakage into relatively small pieces. The recovered stonework must also represent only a small proportion of the total volume of stonework from the first temple which was sufficiently large to possess monumental sandstone columns. The demolition must also have yielded hundreds, perhaps thousands of talatat blocks. Pieces broke from some of them, and workmen knocked off the cylindrical mouldings from corner blocks. But the bulk of the blocks are conspicuously missing from the rubble layer. A great many of them could have been used as fill for the several pylons that separated the courts of the later temple. It is likely, therefore, that a proportion of the Amarna blocks found re-used at other places, most notably at Hermopolis (El-Ashmunein), had been re-used previously.

The southern part of area E takes us to the northern limit of the field of 920 mud-brick offering-tables. Time does not allow us to extend the excavation further south this season, to verify how these offering-tables stand in relation to the mud-brick floor of the earlier temple. To judge from an unpublished Pendlebury photograph, they lay inside this layer of rubble fill and must surely, therefore, have stood on the earlier mud floor. This would represent the same stratigraphic relationship found on the north side of the temple, in area D.

This implies that the reconstructions of the second temple that show the field of mud-brick offering-tables on one or both sides are wrong. The tables belong instead to an earlier temple layout. They had been buried and must have been invisible by the time that the second temple was built. It was into this flat terrace that the gypsum-lined circular basins were made.

This implies that the reconstructions of the second temple that show the field of mud-brick offering-tables on one or both sides are wrong. The tables belong instead to an earlier temple layout. They had been buried and must have been invisible by the time that the second temple was built. It was into this flat terrace that the gypsum-lined circular basins were made.Various features of the earlier temple layout are associated with a floor of mud plaster laid directly over the natural desert surface. The southerly exploration trench in area E (square L26) revealed a shallow grave cut into this floor, containing the burial of a child originally in a stick coffin. Beneath the head, and originally in front of the neck, lay a small and badly made faience amulet in the shape of a deity. The details are hard to discern but it could be a representation of the god Ptah, although there are other possibilities. Its style is reminiscent of later periods when deity amulets were common. The grave was, however, sealed beneath a layer of debris that includes stone pieces (including the female torso) that showed no signs of disturbance. The natural interpretation of the stratigraphy is that the burial was made before work on the second temple began, and thus within the Amarna Period.

Much of the material that is dug, sieved and moved by our workmen is spoil from previous excavations. It continues to produce a surprising quantity of finds, mostly carved stonework but regularly also fragments of faience inlays. As just explained, however, the small extension southwards into ground untouched by previous expeditions (primarily square L26 in area E), quickly encountered a patch of carved stonework that included the fine torso of a royal woman. Exploring this ground further will be an aim of future seasons. This current report is very much about progress across an architectural layout, but this will, in time, be complemented with an account of the objects found, including the sculpture.

As the results of our own re-investigation of the Great Aten Temple accumulate, it is possible to see the signs of two somewhat different dynamics emerging. There is the one that we expect: the drive to create a single temple along classic lines, monumental in scale and symmetrical about an approximate east-west axis. It gave rise, in some of the rock tombs, to pictures that show a completed Aten temple, with a functioning cult. It saw a major rebuild that included the colonnade of colossal sandstone columns in front of the stone façade of the renewed temple. The huge foundation platforms of gypsum concrete have no parallel at the Small Aten Temple and this could be a sign of concern raised by structural weakness at the earlier colonnade, perhaps even its collapse. In order to rebuild the colonnade on its new site, probably further to the west than its predecessor, a huge box was created by building a mud-brick surrounding wall, about 3 m thick, with an equally broad access ramp at the north-west corner. The box itself could have been filled with sand. Once the colonnade was completed, the wall and ramp were taken down, the bricks perhaps supplying a good part of the fill that created the new, raised ground level, the sand (that was mixed with broken pieces of stonework) perhaps used for the fill of the stone offering-table courts to the east.

As the results of our own re-investigation of the Great Aten Temple accumulate, it is possible to see the signs of two somewhat different dynamics emerging. There is the one that we expect: the drive to create a single temple along classic lines, monumental in scale and symmetrical about an approximate east-west axis. It gave rise, in some of the rock tombs, to pictures that show a completed Aten temple, with a functioning cult. It saw a major rebuild that included the colonnade of colossal sandstone columns in front of the stone façade of the renewed temple. The huge foundation platforms of gypsum concrete have no parallel at the Small Aten Temple and this could be a sign of concern raised by structural weakness at the earlier colonnade, perhaps even its collapse. In order to rebuild the colonnade on its new site, probably further to the west than its predecessor, a huge box was created by building a mud-brick surrounding wall, about 3 m thick, with an equally broad access ramp at the north-west corner. The box itself could have been filled with sand. Once the colonnade was completed, the wall and ramp were taken down, the bricks perhaps supplying a good part of the fill that created the new, raised ground level, the sand (that was mixed with broken pieces of stonework) perhaps used for the fill of the stone offering-table courts to the east. The other dynamic was played out on the mud-paved areas that surrounded the stone buildings. Its most lasting manifestation was the sets of gypsum-lined basins. They follow different patterns of layout, were aligned only approximately to one another, were regularly replastered, sometimes subdivided further and were also taken out of use by filling with mud and raising the floor level around them. They appear along the axis of the temple on the early mud floor, and perpendicular to it, to north and south, on the later mud floor. Another basin design, deeper and circular, makes two appearances cut into the later floor.

Then there are the offering-tables that were built on the lower mud floor. The finding of mud-brick offering-tables on the north does not quite confirm that they formed a mirror-image set to those on the south. On the limited evidence so far available, they were smaller, they lay closer to the outline of the later temple and, although there is still much ground to be tested, it looks as if the twin lines of thick gypsum bases for stone offering-tables built on the lower mud floor to the south were not duplicated on the north. If the two fields of offering-tables, on the north and on the south, were not identical, how can we be sure that they were built and used at the same time? Should we start to think that the outside spaces had a history of use of their own, with their own rules for spatial arrangement, separate from the history of the formal stone buildings? One visitor placed a child’s burial in a shallow grave under the floor beside the southern ones.

Then there are the offering-tables that were built on the lower mud floor. The finding of mud-brick offering-tables on the north does not quite confirm that they formed a mirror-image set to those on the south. On the limited evidence so far available, they were smaller, they lay closer to the outline of the later temple and, although there is still much ground to be tested, it looks as if the twin lines of thick gypsum bases for stone offering-tables built on the lower mud floor to the south were not duplicated on the north. If the two fields of offering-tables, on the north and on the south, were not identical, how can we be sure that they were built and used at the same time? Should we start to think that the outside spaces had a history of use of their own, with their own rules for spatial arrangement, separate from the history of the formal stone buildings? One visitor placed a child’s burial in a shallow grave under the floor beside the southern ones.The second formal temple dominates the site. It size and formality encourage the creation of a rigid history of architectural phases valid for the whole ensemble. Its creation was, however, somewhat late in the Amarna Period. We should allow for the possibility that the different parts of the site (including the area towards the rear – the Stela Site – that was examined in 2012) saw repeated or singular ceremonial events that were independently generated or inspired and did not necessarily coincide with the plans to create the huge layout that, for a relatively short time, was the monumental heart of the cult of the Aten.

This leads to the question, to what extent did the huge mud-brick enclosure accommodate expressions of piety by people outside the royal family? Did it serve at least a segment of the population of the city and offer them scope for rituals of their own? The amount of ground to be investigated in pursuit of answers is huge. We may be at only an early stage in understanding this strange ritual layout.

As the re-examination of the temple goes ahead, the team of builders works on the reconstruction. One job is the laying out at ground level of the northern set of large column bases on their foundation platform of gypsum concrete (Area F). Another is the making and laying of new mud bricks that will provide a protective capping to the outer pylons. Between the mud-brick pylons, a stone pavement reached by a ramp recreates the original entrance to the temple enclosure. The builders are also making a low stone retaining wall around the edge of the excavation on the west that will define the front of the site and hold up the embanked debris along this side.

Several members of the expedition have come to work within the expedition house. Andy Boyce completed nearly a month of drawing finds both from the South Tombs Cemetery and from the temple. Alexandra Winkels, on a research visit, was able to set up a portable laboratory in the house that allowed her to pursue her scientific studies of ancient plasters, especially those that go under the heading ‘gypsum’. Marsha Hill and Kristin Thompson have continued their studies on the statues and other hard stone pieces of sculpture that we have stored in the site magazine. Geologist Jim Harrell has made a return visit to investigate sources of gypsum and indurated limestone. Jackie Williamson has been able to visit and discuss her work at Kom el-Nana as a result of involvement with a new film being made on the subject of Queen Nefertiti.

Several members of the expedition have come to work within the expedition house. Andy Boyce completed nearly a month of drawing finds both from the South Tombs Cemetery and from the temple. Alexandra Winkels, on a research visit, was able to set up a portable laboratory in the house that allowed her to pursue her scientific studies of ancient plasters, especially those that go under the heading ‘gypsum’. Marsha Hill and Kristin Thompson have continued their studies on the statues and other hard stone pieces of sculpture that we have stored in the site magazine. Geologist Jim Harrell has made a return visit to investigate sources of gypsum and indurated limestone. Jackie Williamson has been able to visit and discuss her work at Kom el-Nana as a result of involvement with a new film being made on the subject of Queen Nefertiti.During the time that the expedition has been working at Amarna, the project to scan the excavation archive has continued to make steady progress in the Cairo office.

As always, we wish to express our thanks to the generosity of our supporters, and also to the Ministry of State for Antiquities for their permission to continue at the site and for facilities granted.

Barry Kemp/Anna Stevens 11 April 2014

Pictures

Map. The underlying map is that of the Egypt Exploration Society 1932 season. Details from the 2012 and 2013 seasons have been overlaid. Red lines indicate the areas of the 2014 work.

1. IMG_6537: area A: view northwards of the mud-brick pylon after the final removal of 1932 spoil heaps. Photo by Miriam Bertram.

2. P1010172: area B: the two main periods of the temple. On the left (square M31) is a set of gypsum-lined basins cut into the floor of the first temple, along its axis. To the right is a trench for the stone wall of the second temple that has been dug through the basins. In the background is the partially completed reconstruction of the foundations for eight monumental columns that had stood in front of the outermost stone pylon of the second temple. View to the north.

3. P 1000847: area C: a further set of gypsum-lined basins partially uncovered, dug into the floor of the second temple. View to the north-east.

4. P1000946: area D: view southwards across the foundations of what was probably a mud-brick construction ramp and associated walling used in the erection of the columns of the second temple. It was built over the mud floor of the first temple which bears the remains of mud-brick offering-tables. The ground has been cut by burial pits of the early modern period.

5. IMG_6595: area D: detailed view, to the east, of one of the mud-brick offering-tables constructed on the mud-floor of the first temple. Beside it an area of the white-plastered floor is preserved. The overlying brickwork at the top of the picture belongs to the probable construction ramp of the second temple. An early modern grave pit is on the left. Photo by Delphine Driaux.

6. IMG_6186: area E: view eastwards of part of the double line of gypsum foundations for offering-tables belonging to the first temple. Photo by Anna Hodgkinson.

7. P1010034: the brickmaking team.

8. P1010159: repairs to the northern mud-brick pylon and re-creation of the stone threshold.

9. P1010156: repairs to the access ramp to the mud-brick pylon entrance, and laying the stones of the new threshold. At the left edge is the unfinished revetment that will define the western edge of the site.

- Work At Amarna In March 2013

With thanks to Barry Kemp and Anna Stevens for the latest Amarna update. Apologies that the images at then end are not in the right order but you will find that the figure numbers correspond to the captions. The first part of the 2013 season ended...

- Amarna 2013 Begins

2013 STARTUP It has proved possible to resume fieldwork at Amarna. Barry Kemp and a small team traveled to the expedition house on Wednesday, January 30th and began work on site on Saturday, February 2nd, with 20 local workmen, mostly from El-Till and...

- Autumn Field School At Amarna

The latest news update from Professor Barry Kemp, from the Amarna Project. On October 14th the current Amarna field school began to assemble, five overseas students and seven SCA inspectors (drawn mostly from the Middle Egypt region) converging on the...

- A Report On Work Recently Completed At Amarna, Spring 2012

By Barry Kemp A REPORT ON WORK RECENTLY COMPLETED AT AMARNA, SPRING 2012 Figure 1 (see captions at end of article)On the last day of March we resumed our fieldwork. The chosen place was the site of the Great Aten Temple, that lies immediately beside...

- Amarna Field School And News

www.amarnatrust.com and www.amarnaproject.com Update by Barry Kemp, 4 March 2012: FIELD SCHOOL As a follow-on from last year's Amarna field school, we are holding another this year, between October 14th and November 22nd (five weeks). Again it will...